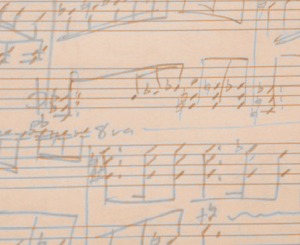

by Matthew Roy, University of California (Santa Barbara). Illustration by Christi Williams (from Chapter Six, ‘She Laughs Too Much’).

Of all the pieces in The Light Princess Suite, the musical characterization of the Princess proved the most difficult. The challenge lies in MacDonald’s subtle subversion of the classical effects of fairy tale curses. The machinations of the vindictive fairy Makemnoit are potent but subtle (see Gabelman on Chapter 3); the fount-side spell does not render the Princess comatose (like Perrault’s ‘La belle au bois dormant’) nor transmogrified (like d’Aulnoy’s ‘La biche au bois’), but rather does something altogether more confounding: it renders her “a fifth imponderable body, sharing all the other properties of the ponderable” (see McLean on Chapter 7). How to translate this fragile yet dynamic double-state into music? It would not be enough to use the formal dance rhythms that give order and weight to her parents’ music (see ‘The King and Queen’). For one, she cannot physically dance, lacking the gravity needed to take actual steps, and secondly, her incessant laughter and lack of seriousness flies in the face of the proprietary rituals that courtly dancing sought to instantiate and maintain. Her weightlessness precludes her humanity.

Chapter Six ‘She Laughs Too Much’: ‘It happened several times, when her father and mother were holding a consultation about her in private, that they were interrupted by vainly repressed outbursts of laughter over their heads; and looking up with indignation, saw her floating at full length in the air above them, whence she regarded them with the most comical appreciation of the position.’

On the other hand, it would be equally incorrect to characterize her exclusively by the elusive and unruly patterns of nature (see ‘Lagobel’). As much as she merits being described alternately as a butterfly, a laughter-cloud, a sea-bird, a Mercurian, or a mermaid, she is undeniably a woman, a Princess, a human. Her humanity problematizes her weightlessness. I have translated these conceptual tensions into musical tensions, making ‘The Princess’ a vibrantly unpredictable sonic experience as the ponderable and the imponderable struggle for presence, definition, and resolution. It wouldn’t do to give a blow by blow narrative of this rambunctious piece with its conflicting multivalencies. Rather, I here present some of my own interpretations of given musical events:

1. Weightlessness – the upper register of the piano receives the most attention, metric acrobatics and harmonic absurdities keep the piece ungrounded rhythmically and tonally, melodies appear as run-on sentences or disconnected fragments (see the late-Romantic piano works of Karg-Elert )

2. Laughter – stifled giggles, immoderate guffaws, and one outburst where perhaps “she could contain herself no longer, and went into the most undignified contortions for relief, shrieking, positively screeching with laughter (see Chettle on Chapter 6 and Debussy’s les fées sont d’exquises danseuses)

3. Curse – the crunchy cluster of notes that growls unexpectedly in the bass register gives a sinister twist to the piece, clouding the beginning in ambiguity, and twice signaling an unruly and derailing outburst of laughter (the second instance is marked Morbidezza in the score; also see Shostakovich’s Prelude in C Major, op. 24).

4. Imposed Propriety – fragments of a simple waltz make a half-hearted appearance, creating the absurd impression of the Princess “put[ting] herself in an armchair, in a sitting posture” in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to “behave herself with dignity” (see Zaderatsky’s Prelude in C# minor [3:20]).

5. Climax – right before the piece ends there is a sudden moment of clarity with unambiguous tonality, powerful chords in a waltzing rhythm, loud and triumphant dynamics, and a grand yet brief melodic gesture. This moment signals the briefest hint of the potential for the Princess’ cure. Not only is it more sturdy and grounded, but through musical quotation it presents a complex package of interpretational meaning. The three measure melody is derived from the opening bars of a choral/orchestral ballade by the French Romantic composer Berlioz entitled Sara la beigneuse, op. 11 (see a piano version), which is a setting of Victor Hugo’s poem of the same name (see a translation). The poem sensuously depicts a bemused and indolent young beauty daydreaming in a hammock by a pool; the interaction between watery reflection and the formation of selfhood speaks to the genesis of the Princess’ desire for gravity as she states, “Oh! if I had my gravity… I would flash off this balcony like a long white sea-bird, headlong into the darling wetness.”

6. Conclusion – resolution is staunchly frustrated, the piece ends in a swath of ambiguity, leaving the dissolution of this enchantment’s tensions for another time.

Works Cited

MacDonald, George. The Complete Fairy Tales. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

Pingback: ‘The Light Princess Suite’: No. 4. “Princess Makemnoit and the White Snake of Darkness” | Subverting Laughter:·